우크라이나 사태로 본 국제역학관계의 지각변동(SCMP)

The foreign ministers of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa met virtually for the BRICS summit recently, the first since the start of the conflict in Ukraine.

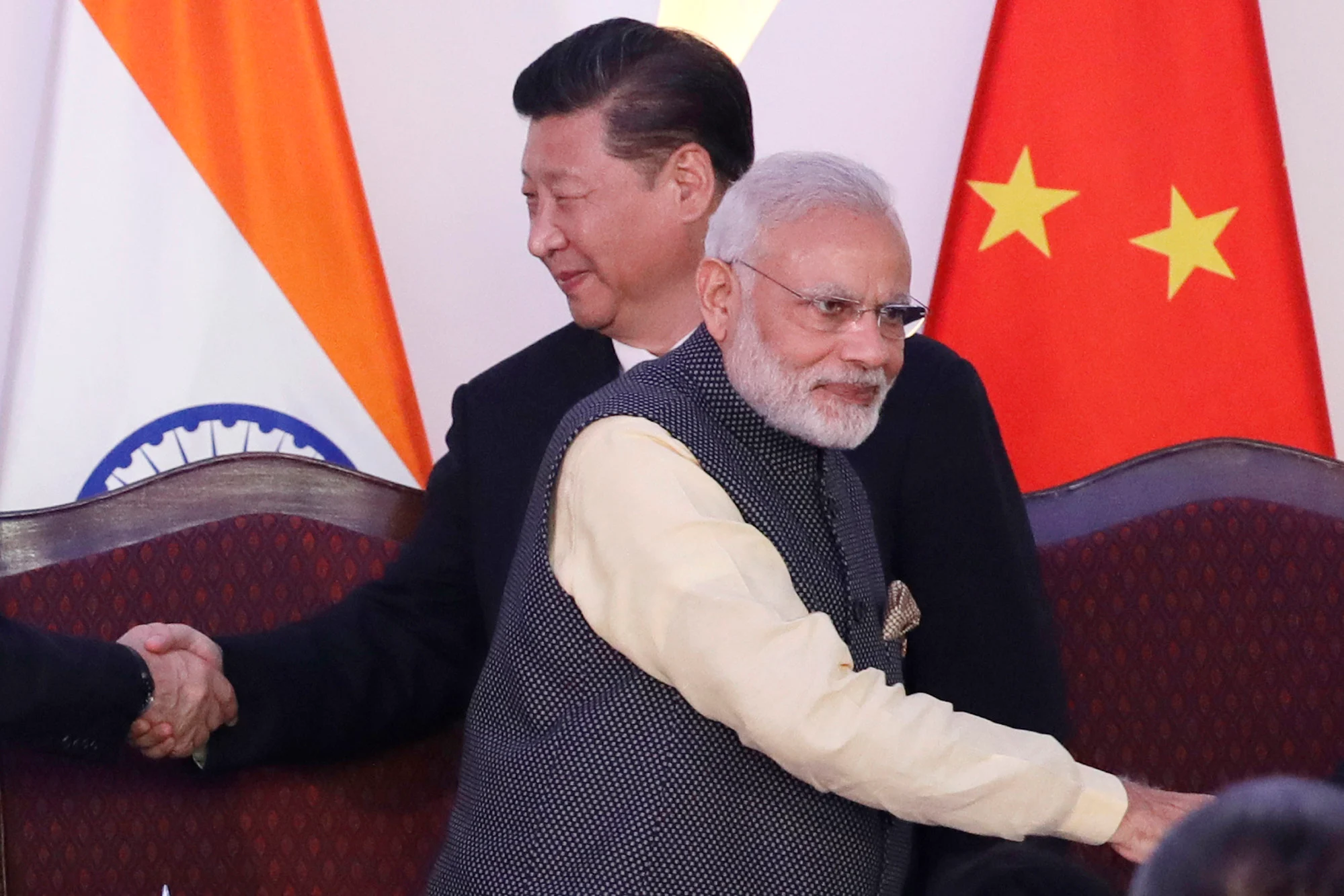

This summit was unique for a number of reasons. First, there had been growing speculation that India would not attend because of its differences with China and warming ties with the United States.

Second, the summit brought together the five nations to discuss security and responses to global crises, among other issues, just as three of them – Russia, India and China – were facing crises at home. India is facing double-digit inflation growth, China has been forced into strict Covid-19 lockdowns and Russia’s war on Ukraine has brought its own economy to its knees.

Third, China has proposed an expansion of the BRICS grouping to include other emerging economies. Interestingly, foreign ministers or their representatives from Argentina, Egypt, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Nigeria, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Senegal and Thailand joined this year’s summit.

Putting an end to the rumours, India did attend the summit and its policy of multi-alignment remains unshaken. However, the other two developments signal the group’s rapidly growing significance and show an attempt to create an alternative bloc to the post-war Western system.

The actions of BRICS nations, individually more than collectively, such as helping countries in need and resisting Western criticism of their foreign policies, suggest a growing desire for a parallel mechanism.

The impact of rising commodity prices, including for wheat and crude oil, is being felt more sharply in the poorer economies of the Global South than in the West, and there has been growing sentiment that the rise was a product of the West’s unilateral sanctions on Russia, leaving countries across the Global South to fend for themselves.

Most recently, India supplied petrol and diesel to Sri Lanka, which is battling unrest and bankruptcy. At the peak of the Covid-19 pandemic, when China, India and Russia rushed to supply vaccines to the Global South, the US held back and the Biden administration took time to find methods to circumvent the Trump administration’s ban on vaccines exports.

Indian foreign minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar’s riposte to media questions last month about his county’s position on Ukraine was a clear sign that New Delhi was not going to jump on the Western bandwagon any time soon.

Similarly, decades ago, India agreed to supply Brazil with cheaper generic drugs for Aids treatment after price talks broke down with US drug maker Merck & Co. Brazil’s HIV/Aids crisis could have been much worse if not for India’s timely help.

Over the past two decades, while the West has courted India through trade, the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue and other multilateral groupings, its position as a former colony and a leader of the non-aligned movement make an allegiance with the West unlikely.

Similarly, Brazil’s policy of having its feet in both worlds may not change any time soon. In the past, its socialist leadership has influenced its friendships and partners. While President Jair Bolsonaro’s cozying up to former US president Donald Trump, and therefore towards America and the West, should not be discounted, Brazil did not cut ties with China or dance to the tunes of the West.

As its foreign minister made clear recently, it will not be joining the West in condemning Russia for its invasion of Ukraine.

China is the leader of this movement. Other than offering vaccine diplomacy, China’s diplomats have hit out at what they see as the West’s hypocrisy on human rights, including Australian military misconduct in Afghanistan, and the US “war on terror” in Iraq and Afghanistan.

China is often the first to establish diplomatic relations with countries shunned by the West, the latest being the Taliban’s Afghanistan. China’s trillion-dollar Belt and Road Initiative runs predominantly across the developing world, providing much-needed infrastructure and investment.

South Africa is no different from the other four in that it has not buckled under Western pressure to condemn Russia.

As for Russia, it continues to have the most to gain from strengthening groupings such as BRICS. Given its economic isolation and military losses, the ailing nation cannot afford to lose partners in the Global South that have either stood at its side or have abstained from voting against it in multilateral platforms.

While the cause of supporting postcolonial societies could be a galvanising force, the China-India border dispute could become a perennial threat to any coordinated BRICS effort. Nevertheless, the likes of the New Development Bank and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank have so far been able to go about their work, shielded from bilateral disputes.

A day after the BRICS summit concluded, US President Joe Biden made his inaugural visit to Asia. He has a tough job trying to sell his Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) to a part of the world that already has two massive trade blocs – the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership.

The IPEF, which is merely a framework without provisions for access to the US market, may not be the most enticing offer for Asian nations after Biden’s promise that “America is back”.

In the next few months, as the global economy goes on a tumultuous ride, the appeal of Biden’s economic framework and the role of BRICS in global affairs will become clearer.

Akhil Ramesh is a fellow at the Pacific Forum